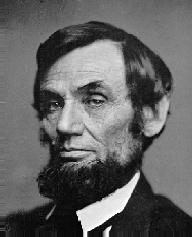

President Lincoln - 1862 |

Copyright Albert Kaplan 1983 (click on image for the full daguerreotype plate) |

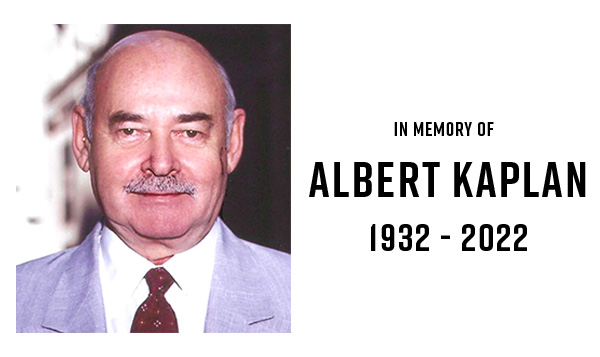

In 1977 Albert Kaplan purchased the daguerreotype receipted as "Portrait of a Young Man" from an art gallery in New York. "When I first saw it I thought that there were similarities between the handsome, aristocratic, and tastefully groomed young man of the daguerreotype, and my mental image of President Lincoln."

Over the years Kaplan researched and assembled materials which cast light on the physical man, Lincoln. Kaplan believed that the best qualified people to analyze the image, and the assembled materials, to consider whether the daguerreotype is of Abraham Lincoln, would be plastic and reconstructive surgeons who work with the human face. In 1987 Kaplan, then living in Paris, sought out Dr. Claude N. Frechette, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon at the American Hospital in Paris, whose report "A New Lincoln Image" is here included. A second report, "Artifact Description of Kaplan Daguerreotype", is by Grant B. Romer, Conservator of the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography & Film in Rochester, New York.

The only other known, and hitherto earliest, daguerreotype of Lincoln, Meserve #1, in the possession of the Library of Congress, was a gift of Robert Todd Lincoln to Frederick Hill Meserve. Meserve reported that "Lincoln believed it was made in Washington in 1848".

In 1965, the New York Academy of Sciences published "Abraham Lincoln's Philosophy Of Common Sense - An Analytical Biography of a Great Mind", by Edward J. Kempf, M.D., a neurologist and psychiatrist whose interest in Lincoln began when he first saw the Volk life mask, from which he inferred that Lincoln must have suffered a serious cranial injury in childhood. After investigating further, Dr. Kempf found Lincoln's own account of having been kicked in the forehead by a horse at age 10 years and "thought dead for awhile." The nature of the cerebral damage, and how it might have influenced the development of Lincoln's personality and mind became a question of absorbing interest to the author. The resulting analytical biography was the product of the author's 12 subsequent years of research.

Because the trauma-induced deformations of Lincoln's face, distinctly described by Dr. Kempf, are seen unmistakably in the Kaplan daguerreotype, providing in themselves definitive, certain, evidence of the daguerreotype's authenticity, we reprint the Kempf analysis (from the title page to the end of Chapter I of Volume I).

An earlier Kempf study of Lincoln's cranial injury appeared in the April 1952 American Medical Association (AMA) Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, Volume 67, Number 4, entitled, "Abraham Lincoln's Organic and Emotional Neurosis".